The NZCBS Pilot: Peeling back the layers

Nial Parkash

Design & Construction (RIBA 4-5)

The NZCBS Pilot: Peeling back the layers

The UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard (NZCBS) is the result of a collaborative effort by some of the biggest players in the UK construction industry, including the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS), the Institution of Structural Engineers, and the Building Research Establishment (BRE).

Released in September last year, the Pilot version sets a stringent framework of embodied and operational carbon limits, along with comprehensive reporting metrics—the most detailed benchmarks available to date. This document is seen as a potential precursor to the much-anticipated Part Z building regulation, which would impose mandatory embodied and operational carbon limits for new projects, directly addressing the Government’s ambitious Net Zero commitments.

Given its significance, it’s astonishing that the NZCBS was developed entirely by a group of dedicated professionals working independently, with no financial support from the Government—but that’s a story for another time.

Due to the length of the NZCBS this article will only attempt to discuss the first half of the document, which focusses on embodied carbon. And before we take a look at our comments, it is worth first stating that the premise around accurately measuring the carbon of buildings is a fantastic one – both for encouraging the reduction of carbon throughout the design process, and for gaining an accurate picture for the performance of new buildings for benchmarking purposes.

We’ve identified a number of recurring themes that should be considered by project teams and clients, as they may affect the feasibility of conforming to the standard (which, for now, is still a voluntary one). They include:

Cost

One aspect that stood out to us was the sheer breadth and depth of analyses required to assess embodied carbon in compliance with the Standard. For comparison, consider a traditional Whole Life Carbon Assessment (WLCA), compliant with RICS PS v2, typically carried out at the post-completion stage against existing benchmarks. In this case, all information is consolidated within a single analysis, often accompanied by a mirrored study to account for the effects of grid decarbonisation.

Now let’s consider a NZCBS study, which, for a building predominantly used as an office, would need to address the following:

- Whole building RICS compliant WLCA (non-decarbonised scenario)

- Whole building RICS compliant WLCA (decarbonised scenario)

- Shell and core LCA

- Cat A LCA (a step beyond shell and core, with basic mechanical and electrical fittings)

- Cat B LCA (fully fitted space)

- An LCA showing the product stage (A1-A3) carbon factors swapped out for structural concrete, steel, and façade aluminium

- List of total mass (kg) of cementitious materials, steel, and aluminium

- LCA of renewable on-site electricity generation equipment

This level of detailed measurement and consideration represents a significant advancement in WLCA. However, it also introduces considerable complexity. As we know, increased complexity often brings increased costs. Broadening the assessment scope inevitably raises costs for the client, which may ultimately filter down to the building’s end-user.

For the time being, the NZCBS remains a voluntary scheme. This means already stretched client-side teams may struggle to justify signing off on additional fees, especially if they have already invested in compliance with other requirements such as BREEAM Mat01 or Greater London Authority (GLA) LCA assessments at various design stages.

The use-type of the building (e.g., Office, Residential, Commercial) appears to significantly influence the extent of output required for compliance. This, in turn, is likely to have a substantial impact on the cost of analysis. Could this lead to a higher number of submissions for use-types with less demanding output requirements? And what implications might this have for the robustness of future benchmarks across different use-types?

Limits & Targets

It’s hard to miss the tables of upfront embodied carbon limits shown in Annex A of the Standard. They show an unprecedented array of building use-types (for both new construction and retrofit), with embodied carbon limits that reduce in increments annually towards a minimal amount in 2050. The 2025 limits have been calculated in a manner that make them realistic and achievable for today’s buildings.

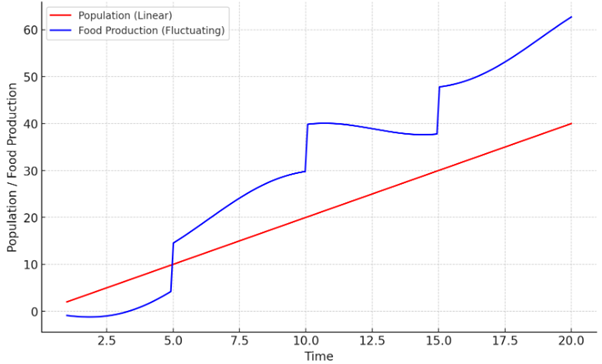

We’d love to be able to peak behind the curtain and have a glance at the methodology for the incremental, almost linear, reduction in the targets. Based on our experience, we know that the development and adoption of low-carbon construction materials doesn’t follow a linear trajectory. This may lead to a Malthusian-like disparity in building performance against the NZCBS benchmarks.

In the late 18th century, Thomas Malthus proposed a hypothesis that described the relationship between linear population growth and an inconsistent rise in food production, which only accelerated with technological breakthroughs. In other words, Malthus suggested that the only times in history when food production met global food demand was when a ground-breaking new method of farming was invented, before the ever-rising population outstripped supply again until the next invention.

Let’s reverse this idea: the steadily decreasing NZCBS upfront carbon limits can be seen as the inverse of Malthus’s population growth line, while the sporadic increases in food production can be inverted to reflect the construction industry’s capacity to drastically reduce carbon emissions.

In this hypothetical scenario, buildings completed during periods of breakthrough innovations—such as ultra-low-carbon concrete, steel, or widely adopted, commercially viable circular economy / material bank schemes—could meet the ambitious carbon limits during those years. However, these advances may soon be outpaced by the steadily decreasing NZCBS limits, only to be matched again during the next technological breakthrough.

Let’s picture another hypothetical: at some point in the future, the Standard becomes mandated by the building regulations. A proportion of buildings completed around that time submit their final post-completion assessments, only to fail to meet the requirements of the Standard. What then?

The Financial Times write of the potential of ‘stranded assets’ – properties that become unsellable and remain vacant because they don’t meet the standards of the day. Could these buildings be earmarked for demolition before reaching their expected design lifespan? Clearly, the process of compliance management and the phased implementation of a mandated assessment strategy will be crucial in addressing this issue.

The NZCBS provides exactly what the industry needs: a rigorous and accurate framework for assessing the embodied carbon performance of the UK’s built environment. However, there are still areas within the Standard that require further consideration and clarification, which we are confident will be addressed in future versions of the document. After all, this is still just the Pilot version.